Vintage buses from the Bus Preservation Society of Western Australia (BPSWA) often turn up at auto shows and heritage fairs around Perth, and always attract a lot of attention from show visitors.

BPSWA has a large collection of buses, ranging from an old horsedrawn passenger wagon from the early 20th century, through to classic buses from the 1950s to the 1980s. Some of them are immaculately restored, others are a current restoration work in progress, and many are waiting their turn to become future restoration projects.

Members of the older generation reminisce about travelling on buses during their childhood; while younger adults marvel at the cool, retro style of the old buses; and kids love these amazing time machines that look as if they have come straight out of a popular kids’ movie.

Despite the old saying that comparisons are odious, there is one bus in the collection that stands out from the crowd. It isn’t the oldest or the biggest, or even the swishest, but the 1929 Leyland Lion known as Metro No. 22 certainly carries its age most convincingly. The rather squat looking bus has a classic half-cab design, a distinctly curved roofline, large painted signs on the sides reading “Perth-Claremont-Fremantle”, and impressive woodwork inside.

After admiring the bus several times at different events, I decided to visit the BPSWA workshops at Whiteman Park on the eastern side of Perth, to learn more about it. I was lucky enough to have a chat with the society’s archivist, Pat Hallahan, who joined the group in 1984. He had kindly scoured the BPSWA files to find information about Metro No. 22, in preparation for our chat.

History

Fortunately, the history and technical specifications of this fairly rare bus are well known, since this information was documented for the Significance Assessment carried out for the National Library of Australia’s Community Heritage Grants Programme. The chassis, engine, and running gear of Metro 22 were manufactured by the Leyland Motor Company in Lancashire, UK, and shipped to Australia. The body work was constructed in Perth by Campbell & Mannix, and consists of a wood-framed and canvas-covered slatted wooden roof. On the exterior there are steel panels below window level.

The completed bus was delivered new to the Metropolitan Omnibus Company (which is generally known as Metro) of Fremantle, on 28th June, 1929. Metro had a fleet of Leyland Lion and Lioness buses, and this Lion was identified as Metro No. 22. The company operated a bus service between Perth and Fremantle at the time, and that was the route that Metro 22 would have operated on for many years.

The bus remained in service with Metro until December, 1953, when it was sold to the Central Norseman Gold Corporation, about 450km east of Perth. In 1974, the bus was acquired from a farm in Southern Cross, about 370km east of Perth in the West Australian goldfields, where it had been used for agricultural activities like spreading superphosphate.

Restoration

I also had a chat with Glenn Boorn, who carried out the mechanical aspects of the restoration. He explained, “The motor was reconditioned by apprentices at Westrac, the Caterpillar tractor dealer. Metro No. 22 originally had a 4 cylinder, 5.1 litre petrol engine, but was converted to diesel in the 1930s. During the restoration, we turned it back to petrol by installing the engine from Metro No. 24. Installing the new engine was a big job. It had to be in the same line down to the differential, which meant that we had to redo all the mountings.

“The radiator was a mess. We had to reconstruct it by punching out copper discs, and sliding them onto copper tubes to increase the surface area for better cooling. Then we sent them off to have ball bearings forced down the tubes, to expand them for a tighter fit. The rubber seals were made locally. Overheating is a big problem with the petrol engine, though it probably wasn’t such a problem when it had a diesel engine. The fibre couplings on the magneto had been shattered and needed to be replaced. The timing has been out ever since and may be the reason for overheating.

“The crash gearbox makes the bus very difficult to drive. You have to get the revs just right when changing gears. In the past, some drivers are believed to have driven in fourth gear all the time, to avoid changing gears. The engine has so much torque that it can easily drive off from a stationary point in second gear.

“The green box near the engine is a vacuum tank for the fuel, which is gravity-fed into the carburettor. It doesn’t work very well, and we are trying to bypass it. The bus has a crank handle that you use when adjusting the engine, for example, to adjust the timing or tappets, but you can’t use it to start the engine, because the impulse magneto can misfire and give a kickback that can break your arm”.

Glenn pointed out that the bus has its original chassis and suspension. It has all mechanical brakes, which are not so effective, so you sometimes need to use the handbrake as well as the main footbrake. The handbrake operates by pushing the lever forward. The rear brakes have four brake shoes in each drum, two for the handbrake and two for the footbrake. Max Hayles made the wooden steering wheel and the gear knob. The lights are original and have been re-chromed.

Metro No. 22 has seating for 28 passengers, though it may have had 29 when it was new. The restoration commenced in 1998, and was completed in 2005. The project only cost $3,500, because Max got help from other organisations, like Balga TAFE, which rebuilt the seats. He also obtained tyres from Dunlop and built the wooden parts from old timber.

For the Record

Metro No 22 was fully restored by the members of BPSWA about ten years ago.

BPSWA archivist, Pat Hallahan, explained that, “It was restored primarily by Max Hayles, who had the woodworking skills that were required for the project. Glen Boorn did the mechanical stuff, and I worked on it too”.

Pat showed me a series of articles about the restoration that were written by Max Hayles and published in Rattler (the BPSWA newsletter) while the project was in progress. They make very interesting reading and are a valuable resource for anyone wanting to know more about the restoration.

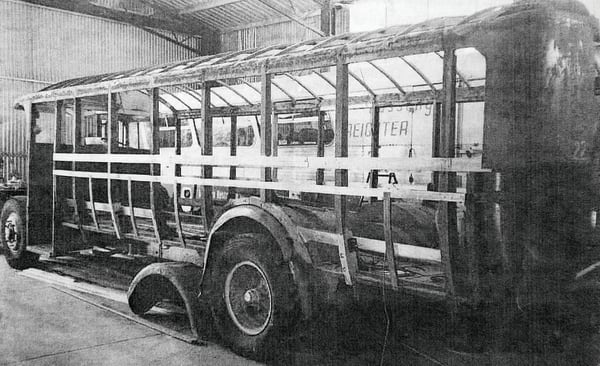

He describes the state of the bus back in 1998 as, “22 was buried in a dingy corner of our depot/workshop. The body had been stripped to the bare frame. It was full of junk and looked in a very sorry state. There was no roof at all. The window glass had all been removed and stored who knows where”.

He goes on to describe how some rotten window pillars were used as patterns to build replicas out of jarrah wood from his “kerbside warehouse”. The wooden roof bows were constructed in the same fashion, using laminated wood obtained from old wooden doors, also from the kerb junk collection.

Removing the damaged diesel engine was a tougher challenge than expected. All parts like the wheel hubs, brake drums and shoes, linkages, vacuum servo, gear lever, wheels and so on, were removed and sandblasted. Max also describes many details of the electrical and mechanical aspects of the restoration, and acknowledges the many individuals and organisations that gave freely of their time, expertise and materials during the project.

In the Driver’s Seat

Metro No. 22 has a half cab design, which means the cabin is a bit cramped and requires a bit of squeezing to get into the driver’s seat. The main controls are fairly standard, with foot pedals for the accelerator, clutch and footbrake, and floor-mounted levers for the gears and handbrake.

The brakes are vacuum servo assisted mechanical drum brakes. The transmission is a 4 speed sliding mesh gearbox with a worm drive differential. The gearbox dates from the days before the invention of synchromesh, and is commonly called a ‘crash gearbox’.

Gauges on the dash include speedometer, ammeter, oil pressure gauge, water temperature and tachometer. The passenger door can be opened and closed from the driver’s seat by means of an overhead lever, which is connected to the door through an impressive series of mechanical linkages.

Second Thoughts

There are no doubts that members of the BPSWA are very proud of their 1929 Leyland Lion. They refer to it as “the jewel in the crown” and “our prime exhibit”. That’s hardly surprising, since this is the only remaining intact, fully rebuilt and refurbished bus from the period in Western Australia. It is also a keenly sought after model internationally.

Whilst much effort went into restoring the bus back to how it appeared on the road in 1929, BPSWA members commented that some compromises were made in its final refurbishment. However, when you stand back and look at Metro No. 22, these compromises aren’t what catch your eye. The bus is simply stunning and carries its age with such confidence, that these imperfections seem rather minor.

The Bus Preservation Society of WA does not have a museum as such, but visitors are welcome at their workshop at Whiteman Park in Perth, anytime from 8am to 1pm on any Tuesday. The society exhibits vehicles at auto shows and heritage fairs in Perth, and in the Revolutions Transport Museum at Whiteman Park. For more information about the organisation, visit their website at www.bpswa.org

*Keith Hall